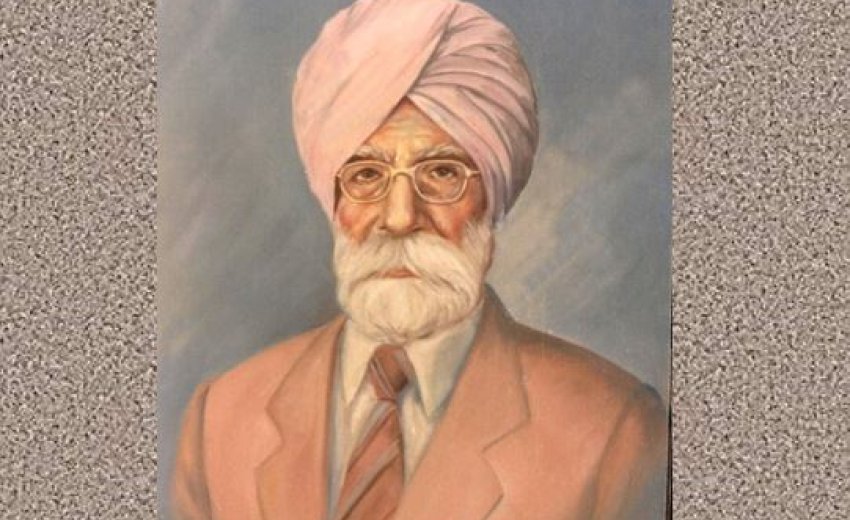

This year one can expect a number of seminars, lectures and theatrical performances in Punjab celebrating the birth centenary of one of the most versatile and innovative of the Punjabi writers of the 20th century. Tejwant Singh Gill's informative, scholarly and comprehensive monograph is the first to begin the process acknowledging Sant Singh Sekhon's literary achievement. The book's modest aim is to provide an introduction to Sekhon's life and works. It is cogently written and should persuade other commentators to evaluate Sekhon's development as a writer, editor of sacred scriptures, translator and literary historian.

This year one can expect a number of seminars, lectures and theatrical performances in Punjab celebrating the birth centenary of one of the most versatile and innovative of the Punjabi writers of the 20th century. Tejwant Singh Gill's informative, scholarly and comprehensive monograph is the first to begin the process acknowledging Sant Singh Sekhon's literary achievement. The book's modest aim is to provide an introduction to Sekhon's life and works. It is cogently written and should persuade other commentators to evaluate Sekhon's development as a writer, editor of sacred scriptures, translator and literary historian.

However, Gill is ambiguous about whether Sekhon should read primarily as a writer of Punjabi literature or be regarded as one who thought of Punjab and Gurumukhi as the exclusive heritage of the Sikhs. Perhaps the fault lies with Sekhon himself who is a progressive thinker and is yet unwilling to sever his relationship with the Sikh tradition of religiosity and heroic self-representation.

Sekhon is magnanimous and non-sectarian enough to applaud Bulle Shah and other Sufis as the foundational poets of Punjab. At the same time, however, he asserts that it was with the establishment of Sikh kingdoms that literary writing in Punjabi acquired its special provenance. Indeed, in his later essays on the history of Punjabi literature and the sacred tradition, Sekhon quietly slides into equating Punjabi writing with the Sikh tradition and suggests that Sikhism alone can overcome the 'fatalism' of the Hindus and the 'oppressiveness' of others.

Sekhon's father belonged to an area where the first Anglo-Sikh war was fought and where Guru Gobind Singh had spent some time. These historical events were so deeply inscribed in Sekhon's sense of his intellectual tradition that his later writings became preoccupied with the historical fate of the Sikhs and their spiritual destiny. This was a surprising transformation in one who was educated at Forman Christian College, Lahore, was once a Communist and was influenced by Freud. Sadly, as Sekhon grew older, he left in the shadowlands of memories the fact that his own autobiography (1989) was withdrawn from circulation because the orthodox found it blasphemous. When I met Sekhon in the 90s, it was difficult to recognise him as the writer whose first play, Eve at Bay (1939), on infidelity and female 'disobedience', had rankled the conservatives by its fascination with the libidinal. It was also intriguing to recall that the man who now denied everything other than the Sikh tradition had once declared that the love of his life was a Finnish woman (reticently identified as "Ms Helmi' by Gill).

Sekhon's first collection of one-act plays in Punjabi (1942) was published when the communal hatred had infected almost everyone. It had a preface by Mohammad Taseer, the Principal of Islamia College, and was written under the political influence of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and the Progressive Writers. Gill mentions these, but doesn't explain why Sekhon, who was once a religious iconoclast and a moral rebel, turned into a Sikh ideologue.

Gill's comments on Sekhon's evolution as a writer, educator, and religious thinker are perceptive. He appreciates Sekhon's use of Freud and sexuality and admires Sekhon's role as a public intellectual. Sekhon had to resign from Khalsa College because he wrote that if sexuality is pushed into the dark recesses of shame, and thereby morally degraded, it inevitably remerges in a variety of personal, social and political pathologies. Estranged from that which is essentially and fundamentally human in men and women, the sexual takes the form of hysteria, lament or irrational hate. Sekhon wrote his texts of sexual betrayal and the pain of instinctual repression, in part at least, as protest against both colonial insolence and the cruelty inherent in sexual asceticismÂespecially in a society where women are required to be chaste while men are expected to be virile.

Sekhon's stories like Murr Vidhwa (Widow Again), Majhadhar (Crosscurrent) pay attention to the moral legitimacy of the demands sexuality makes on us in our struggle to be human in the world. Gill claims, with justice perhaps, that these stories are thematically bold for their times. However, compared with the writings of his contemporaries like Tagore, Manto or Jainendra Kumar, Sekhon's views of sexuality circumscribed within marriage are conventional. Gill, in contrast, thinks that the very theme of sexuality is sufficient to establish Sekhon's place as an explorer of the forbidden.

I wish Gill had told us which of Sekhon's texts would survive the test of time. One suspects, however, that apart from some of his Partition stories, a judgement about the obsolescence of the rest of his work has already been passed. His plays, despite their proclaimed modernity, seem to be old-fashioned moralities, with the writer as a puppeteer who moves his characters around, not to reveal destinies, but to pass judgements and seek our approval. We are not expected to puzzle over their motives and their actions, we are only required to sit back appreciate the clich`E9.

Surprisingly, Gill as a materialist critic doesn't mention the fact that the anti-colonial movement, along with the emergence of a democratic and socialist consensus, had brought with it a new concern for the fate of the ordinary precisely over the same time as Sekhon was searching for new forms for his plays and novels as well as for a philosophy of life which was different from the one prescribed by tradition and orthodoxy.

Sekhon couldn't have been immune to the Gandhian or Nehruvian conviction that in a democracy individuals deserve attention not because they are heroic but because their fears, flawed reasoning, psychic scars, betrayals or survival during political crises make them achingly human. Had Gill read Sekhon thus, he could have made a convincing case for his importance in the Indian literary history as an example of radical changes in the cultural sensibility of his times.

Sant Singh Sekhon by Tejwant Singh Gill. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. Pages 126. Rs 40.

Courtesy: The Tribune - Jagpal Singh Tiwana, Dartmouth, Canada