About ten years ago, I was in Amritsar, Punjab, visiting family and had been invited round for dinner at a relative’s house – a member of the Punjab Police. He told me about a man he had to have a stern talking to earlier that week, but did not arrest because it was a “family matter.” The man, in his 30s, had broken into his uncle’s house to steal a cow tranquilizer. Everyone in the room, including myself, laughed at the absurdity of the crime. When he revealed that the man had injected the cow tranquilizer into his leg to get high, and that this was a “growing problem in Punjab” – his exact words in Punjabi – we were still half-heartedly laughing, but more out of a sense of uneasiness.

About ten years ago, I was in Amritsar, Punjab, visiting family and had been invited round for dinner at a relative’s house – a member of the Punjab Police. He told me about a man he had to have a stern talking to earlier that week, but did not arrest because it was a “family matter.” The man, in his 30s, had broken into his uncle’s house to steal a cow tranquilizer. Everyone in the room, including myself, laughed at the absurdity of the crime. When he revealed that the man had injected the cow tranquilizer into his leg to get high, and that this was a “growing problem in Punjab” – his exact words in Punjabi – we were still half-heartedly laughing, but more out of a sense of uneasiness.

Ten years on, and this case is no longer an anomaly. Stories about Punjabis of all genders, classes, religions, and ages injecting themselves with things like horse respiratory medicine are not even remotely funny. Or uncommon. Virtually everybody in Punjab has a story about drug abuse. 75% of Punjab’s youth is addicted to drugs. 60% of ALL illegal drugs found in India are confiscated in Punjab. Drug abuse in Punjab is no laughing matter, but laughing about alcohol is apparently still okay because the problem in Punjab has nothing to do with alcohol. It’s all about the drugs. Many of this relative’s other stories were and still are more socially acceptable for us to laugh at because they involved drunk Punjabi men falling off tractors or scooters.

And there is no awkwardness at laughing at the following well-executed parody by Jus Reign of the “drunk uncle, who provides for great entertainment” and includes the drunk uncle dancing with a glass on his head, falling down, and generally behaving like an idiot. We don’t see the drunk uncle as having an actual problem. It’s just alcohol, after all, and not anything “serious.” (The section I am referring to starts at 2:41 and ends at 3:25.)

Jus Reign is one of my favorite comedians, not just because his humor is aimed at Punjabis (although that helps), but because he is genuinely funny and tackles issues in a way that doesn’t go for a quick laugh. He sometimes has a social point that he makes, but wraps it up in “comedy” like “WTF Punjabi Music Industry?” (listen at 1:42). The “drunk-unc” sketch is a well executed comedy sketch, but a drunk uncle is different than an alcoholic uncle, when it would hopefully not be funny. Jus Reign’s comedy comes from actual family members and his own observations of life, so, this next question is in earnest: how far off are we from a parody about the irresponsible, but lovable, heroin-addicted uncle?

While drug abuse is completely out in the open in Punjab, it isn’t socially acceptable to casually reference it in popular music originating in Punjab. Right? To clarify, I’m not talking about musicians of Punjabi descent who live in Western Counties and sing their bhangra pop bits, or “Punjabi” rappers like Bohemia, who raps about (amongst other things) doing cocaine, smoking weed, and being estranged from his family members because of it. Or Honey Singh, who is from Punjab and seeks to “bring to light,” some kind of a social message. I’m not exactly sure what that message is, but he’s apparently keeping it real. In “Dope Shope,” he raps/sings about girls on yachts who are inevitably loose, take “dope-shope,” and are solely responsible for tarnishing Punjabiyan di shaan by drinking large quantities of vodka that destroys their livers.

| “Niri suki vodka na mariya karo, thoda bohut Limca vi pa lia karo/ Ainvi mitti vich rol na Punjabiyan di shaan.” |

He even tries to help the girls and their livers out by suggesting they mix their vodka with some Limca. He insists that the overarching message of his songs is rooted in a moral: “if you’re a girl, don’t do dope-shope or drink alcohol straight. It isn’t proper. And is mittying up Punjabiyan di Shaan.”

Like their hip-pop counterparts, they are talented musicians, but the songs really aren’t about any moral issues anymore than “I’ve Got Hoes in Different Area Codes” is about empowering women of different ethnicities. It’s about exaggerating the lifestyle of a playa: parties, fast cars, plenty of bling, and creating a piece of music that is entertaining. And Punjabi musicians are certainly not lacking in the talent department. Honey Singh is talented and has clearly studied the art of 16 bars, effective hooks, and creating an energizing mood throughout the piece. If you can skip the content of his songs, if his talent isn’t obvious, he also has a degree from the prestigious Trinity College of Music, which is no joke. Bohemia, on the other hand took the more street thug approach – he grew up poor in Oakland, lost his mother to cancer, and now apparently lives the thug life, which is what all of his songs are about. Artists like these, and plenty of others like RDB, Nindy Kaur, and a host of others all know their stuff, and deliver on simple, catchy lyrics with a good beat. Try listening to any of their songs and not wanting to sing along, or stomp your feet and yell “bruaahhh.” Try it. Didn’t work, did it? But there aren’t any moral issues at play here. And the real question is, should there be? If they don’t make grand proclamations of getting Punjabis to be aware of Bhagat Singh, and just claim they’re entertainers, does that solve it? Lil Kim or Jay Z or Ludacris don’t have any particularly deep songs. They are just entertainers too, right?

To return to Honey Singh’s “Dope Shope” song for a minute: those who are addicted to drugs in Punjab aren’t getting high to go party on a yacht. They are strung out on the streets, begging for 30-300 rupees to get some knock off synthetic drug to last them a couple of hours. The abuse of drugs for those who live in metropolitan cities in India, or in Western countries, is born out of a totally different experience than what has been ripping through Punjab like a tornado, apparently unnoticed. And now it can’t be ignored. Not by Punjabis. Not by India. And not by the world press.

There is a New York Times article from April 18, 2012 that was severely disappointing in its scope, but a much more in-depth one from just a few days ago from Tehelka is definitely worth reading. Neither of these are exactly “news,” to anyone who has even a mild interest in the state of affairs in Punjab, but this is a rather chilling story. Not just because 75% of Punjab’s youth are addicted to drugs (that’s one addict in every third family). Not even because 60% of all drugs in India are confiscated in Punjab. But because of this: “India’s Election Commission said that some political workers were actually giving away drugs to try to buy votes. More than 110 pounds of heroin and hundreds of thousands of bottles of bootleg liquor were seized in raids. During the elections, party workers in some districts distributed coupons that voters could redeem at pharmacies.”

It’s a sign of manliness in Punjab to go to one of the million thekas littered throughout Punjab – small shops selling legit and bootleg alcohol where Punjabis can get their booze early in the morning or late at night with misspelled generic names like “Scartish Whiskey” manufactured in Uttar Pradesh. Or spend less than a couple rupees and get old school moonshine in plastic packets, with saunf and a limca to wash it down, delivered right to your tractor. It has been so ingrained in our psyche that Punjabi munde should drink massive amounts of alcohol and be able to handle it. That’s why you’ve never heard a song about Punjabi boyz drinking patiala pegs, then stumbling, slurring their words, and vomiting all over each other’s shoes. They’re always coordinated and slurring just enough to be funny and “cute,” but not enough to be unsexy (like PBN’s “Fitteh Moo”).

All of our revered legends of Punjabi music have sung songs in praise of alcohol. From Asa Singh Mastana to Bindrakhia to Gurdas Mann to Malkit Singh. And these days, virtually every single Punjabi singer’s collection features tracks about alcohol and girls. Nobody seems to have anything else to say. But why is it that Punjab is the only state in India that makes it incredibly easy for unregulated alcohol to be sold at thekas? You can find two or three at ever mile marker (I’m not kidding). You don’t see that anywhere in U.P. or Maharashtra or Himachal Pradesh. Is that Pakistan’s fault or some ISA conspiracy?

You can probably name twenty songs dealing with alcohol, but since that is clearly not the problem (Punjab only has a drug problem, you see. That’s what needs to be stopped), I’m going to talk about someone else: Geeta Zaildar, an unlikely segue into my discussion on drugs.

When I first heard Geeta Zaildar’s song “Chitte Suit te Daag Pe Gia,” I thought it was quite catchy. And I have yet to find someone who listens to the song and doesn’t feel like belting out the chorus. In terms of a catchy hook, it’s up there with “duppata tera sat rang da,” “Unhh,” (Biggie) and Kriss Kross’s “Jump.” Okay, maybe those last two were just me. The point is, it is catchy and has the formulaic “hook” that everyone sings along to. He also has a fantastic voice, there is a good beat, and a typical storyline: girl is mock angry with boy because he isn’t paying attention to her; this issue will be resolved by the end of the song, and there is rain.

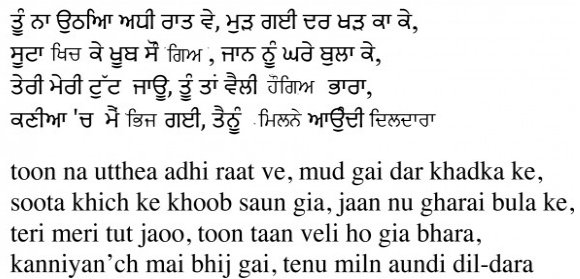

But there was a line in there that surprised me, considering that most of his other songs are standard boy-girl light drama. He doesn’t do those testosterone-filled macho man songs with whiskey spilling from the cups, is never off shooting guns for no reason, or in a night club with or without sunglasses and a crew. But then again, neither was Diljit up until a few years ago (read about it here). Anyway, I listened to the stanza again. Here is a version that someone took the time to translate into English. Overall, they capture the gist of the song, but watch the bit that translates to “You pulled the covers and went to sleep,” followed by “you can gain your freedom.” Not even close to what the Punjabi translates to. Watch from 1:29:

Here are the lyrics in Gurmukhi and Romanized Punjabi:

The word “soota,” is a verb, meaning to inhale smoke. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out what he has been smoking that would knock him out for the entire night, not even waking up when his “jaan” repeatedly bangs on the door, yells at him through the window, and calls him repeatedly on the phone. After he invited her round. The line after that, in good jovial fun, she questions their relationship continuing because he has become not just a “vaili,” (a drug addict), but “vaili ho gia bhara”: he has become a heavy drug addict. But he seems fine after he wakes up, completely functional; he smiles and everything is all good. So, perhaps she was just over-reacting to this Punjabi munda doing what Punjabi munde do: having a little soota here and there? That Miss Pooja – she be tripping.

Is this a new norm for Punjabi songs? Casual references to drugs like it’s no big deal? Just part of the narrative. Like having a peg-sheg, riding a Bullet motorcycle, or whistling at kudiyan on GT Road. Will we still have the girls running through mustard fields in the songs, the men wearing turbans for part of the song, and then taking a break to shoot some heroin or cow tranquilizer? Will they still be wearing their karras to reprezent? Will there be a song from a Punjabi singer equivalent to Afro-Man’s “Because I Got High?” Just another catchy, beat-driven song? Maybe I just need to get with the times and start supporting Punjabi music regardless of what it’s about because it’s in Punjabi, has a good beat, and the lyrics are catchy. It is, after all, only entertainment, and is helping keep the Punjabi language and a semblance of the culture alive (yay?). Nashe Harao: Defeat Intoxicants

Clearly the problem in Punjab then has nothing to do with alcohol. But those drugs, man, that’s where the real problem is. Not soota though. Soota is okay. It’s those Pakistani ISA agents trying to destroy Punjab and those crafty drug smugglers bringing their poisons to Punjab. Nothing to do with our own politicians, who couldn’t possibly be complicit what with those impassioned speeches they’ve been making. Oh wait, last time they said anything about it was . . . during the elections. And the agricultural policies that our politicians put into place couldn’t have anything to do with it. What possible link could there be? Certainly, none. Isolate the problem. Check! Simplify the problem. Check! And then blast it (pending), because that always works out well. Then we can have Apna Punjab again, drink our ghar di sharab (to reiterate: not the problem), and have our mooley with the ganda – is there any other way?

Clearly the problem in Punjab then has nothing to do with alcohol. But those drugs, man, that’s where the real problem is. Not soota though. Soota is okay. It’s those Pakistani ISA agents trying to destroy Punjab and those crafty drug smugglers bringing their poisons to Punjab. Nothing to do with our own politicians, who couldn’t possibly be complicit what with those impassioned speeches they’ve been making. Oh wait, last time they said anything about it was . . . during the elections. And the agricultural policies that our politicians put into place couldn’t have anything to do with it. What possible link could there be? Certainly, none. Isolate the problem. Check! Simplify the problem. Check! And then blast it (pending), because that always works out well. Then we can have Apna Punjab again, drink our ghar di sharab (to reiterate: not the problem), and have our mooley with the ganda – is there any other way?

So the real issue is drugs, and the staggering statistics, like 75% of youth in Punjab are addicted to drugs, and yes that includes the girls, too, when they’re not running through mustard fields in their traditional outfits. Despite these statistics, according to politicians, the solution is actually very simple. In India, it’s all Pakistan’s fault. In Pakistan, it’s all Afghanistan’s fault. Who knows whom Afghanistan will put the blame on. And let’s just forget that there are plenty of places in India and Pakistan where it’s 100% legal to grow opium and marijuana plants, the latter, which grow like weeds all over the country. But let’s just blame the “foreign” smugglers who are crossing over into India with heroin – the drug for those with money, which has given rise to the cheaper alternative “synthetic drugs” – and prescription medicine that is injected into the bloodstream and can deliver highs for several hours.

The other solutions, like de-addiction centers, prey on families who have money and are absolutely desperate to try and help their sons or daughters. Yes, daughters too. Since it isn’t official (not that this means much), many of these centres are unlicensed, and are business-oriented, offering “luxurious facilities” or rapid results, or others that try to beat the addiction out of them using belts, or by getting you addicted to another drug, like Buprenorphine, for repeat business. And unlike detox centers in Western countries, they don’t need to get permission from the addict. A team comes in a van, grabs the son or daughter, and forces them into “treatment.” There are, of course, legitimate de-addiction centers, but the problem goes much deeper than placing blame on one or two things, especially when you have politicians buying votes with drugs and then making speeches about how something must be done about it.

Unemployment is high in Punjab for a variety of reasons, rooted in approved Agricultural laws on both sides of Punjab that have allowed companies like Monsanto to gain a stranglehold on farmers by copyrighting genetically modified seeds, forcing farmers to take out loans to pay for pesticides (amongst many other things). In unrelated news, Monsanto is in Afghanistan and Iraq. And this brought about an influx of loan sharks who took (and continue to take) full advantage of the vulnerable position the farmers are in by charging extortionate rates, ultimately resulting in an epidemic of farmer suicides, whose families then had to deal with the aftermath – psychologically and financially. So it’s not particularly shocking that many of those who are drawn towards drugs (definitely not alcohol though) are from villages and agricultural areas. But using these synthetic drugs has now become more widespread because of its social acceptance, especially amongst the youth, even in towns and cities that aren’t directly connected to agriculture, like Chandigarh. Walk into Punjab University or Khalsa College and odds are you will find someone to supply low grade synthetic drugs, and heroin. Out in the streets of Punjab, nobody can even be bothered to hide it anymore. They’re just out in the alleys, side-streets, open spaces, enclosed spaces, in groups, or alone just doing their thing all over Punjab, from Lahore to Mohali. Even in Amritsar, steps from Harmandir Sahib, the Golden Temple.

Tell me I’m not the only one who sees the parallel between what the government tried to do during the 1980s, but couldn’t because of the ideological movement (contrary to popular belief, violence did not define it). What failed then is working today (for now). Now, when we are told that alcohol is in our D.N.A., part of our cultural heritage, we fully embrace it through music, through parties, through weddings. We sometimes don’t even have qualms with having the wedding ceremony at the Gurdwara in the morning, and getting drunk in the evening for the reception. And what better way to squash any resistance to things that matter than to silence an entire generation by plying them with not just alcohol, but drugs too, effectively guaranteeing they will not be thinking about anything other than where to get their next hit.

Remember that just a year before the revolution in Egypt, people would complain about corruption on every level like it was just one of those things that had to be accepted as part of life. In Punjab, we kick up a fuss every so often by marching in the streets or burning effigies to protest (insert cause here) and then we get sidetracked and forget all about it. In the “West,” we pride ourselves on churning out numbers to protest marches, social media campaigns, but none of this has really sparked a revolution or any meaningful change that I have seen. In two months, thousands of people will pour into the streets with banners condemning the Indian Government for their role in 1984. There will be signs for Khalistan, and Bhai Balwant Singh Rajoana. We will update our status on Facebook and Twitter. And then, we will get sidetracked by something else. Whatever happened to that whole Bhai Balwant Singh Rajoana thing? Did we “win?” (I didn’t get the memo).

Remember that just a year before the revolution in Egypt, people would complain about corruption on every level like it was just one of those things that had to be accepted as part of life. In Punjab, we kick up a fuss every so often by marching in the streets or burning effigies to protest (insert cause here) and then we get sidetracked and forget all about it. In the “West,” we pride ourselves on churning out numbers to protest marches, social media campaigns, but none of this has really sparked a revolution or any meaningful change that I have seen. In two months, thousands of people will pour into the streets with banners condemning the Indian Government for their role in 1984. There will be signs for Khalistan, and Bhai Balwant Singh Rajoana. We will update our status on Facebook and Twitter. And then, we will get sidetracked by something else. Whatever happened to that whole Bhai Balwant Singh Rajoana thing? Did we “win?” (I didn’t get the memo).

During our Gurus’ lifetime, there are obvious differences in the circumstances, but the “nuisances” weren’t so drastically different than they are today. There was religious persecution, an iron clad caste system, and gender inequalities, amongst a list of many other societal “norms.” Guru Nanak Dev Ji never accepted the way things were – none of our Gurus did. They fought for the way things ought to be as individuals, and for the Panth. In different ways, they fought for the rights of others and some of our Gurus laid down their lives for this basic human right, not just for themselves, but for all human beings, regardless of their beliefs. And these basic human rights – to live with dignity, free from oppression are being -what feels like – systematically deprived specifically in Punjab. Elsewhere, you don’t find thekas so easily accessible outside offices, schools, places of worship, residential areas. But you do in Punjab. This strategy is not new. You don’t find this in Maharastra. You don’t find this in Goa, or Kerala. Or anywhere else in the country. And they drink plenty of alcohol, and even have their own version of turra (moonshine).

The revolutionary spirit extends beyond what our Gurus accomplished as individuals, but what they contributed for the Panth. It lies in every poetic verse, raag, and the powerful concepts in the Guru Granth Sahib, which were all well ahead of their time, and still cannot be fully grasped, such as the idea that God exists within all of us mere mortals. But what our Gurus contributed through the Guru Granth Sahib is revolutionary in its own right as a body of work that incorporates not just the wisdom from our Sikh Gurus, but shabads from Muslim and Hindu Bhagats. No other religious text has ever attempted to include ideas from those of other faiths, or to give credence to the idea that there are many paths towards God. There are no passages in the Guru Granth Sahib that threaten someone who isn’t Sikh with burning in the fiery pits of hell or not being able to reach salvation. That idea in itself is revolutionary.

The revolutionary spirit extends beyond what our Gurus accomplished as individuals, but what they contributed for the Panth. It lies in every poetic verse, raag, and the powerful concepts in the Guru Granth Sahib, which were all well ahead of their time, and still cannot be fully grasped, such as the idea that God exists within all of us mere mortals. But what our Gurus contributed through the Guru Granth Sahib is revolutionary in its own right as a body of work that incorporates not just the wisdom from our Sikh Gurus, but shabads from Muslim and Hindu Bhagats. No other religious text has ever attempted to include ideas from those of other faiths, or to give credence to the idea that there are many paths towards God. There are no passages in the Guru Granth Sahib that threaten someone who isn’t Sikh with burning in the fiery pits of hell or not being able to reach salvation. That idea in itself is revolutionary.

Our Gurus encouraged us all to think and question the world we were born into, and never simply accept things the way they are, but to constantly strive towards how we know things should be based on the teachings of our Gurus. But there don’t seem to be any significant questions from our generation coming out of Punjab, particularly in the arts. Outside of Punjab, there is at least a ripple. There have been some incredibly courageous people in Punjab (not of our generation though) who have sought to change things in their own way, like human rights activist, Jaswant Singh Khalra, Sardar Gursharan Singh, who brought real issues to the streets of Punjab through theater, and Bhagat Puran Singh, who was 19 when he informally began Pingalwara – a home for the destitute and “unwanteds” of Punjab. But these people are gone now.

Outside of Punjab, there are musicians like Humble the Poet, Jagmeet “Hoodini” Singh, Tanmit Singh of G.N.E., Sikh Knowledge, and Mandeep Sethi, who use their connection to Sikhi to rap about some issues in Punjab, but it is primarily about issues of a more universal nature, or about their experiences living in North America. They have proven that having a beard and a turban, while rapping about real issues and staying true to their ideals can garner a significant audience. And there are musicians and writers of the older generation also who sing and write in Punjabi on issues like female foeticide, or partition, as it relates to them as N.R.I.s, like my father, Punjabi poet and singer Pashaura Singh Dhillon. As with writers like Neesha Meminger, or Nav K Gill, who have watered down the complexity of 1984 to make it palatable to a Young Adult audience outside of Punjab. Or Shonali Bose and Bedabrata Pain, who made the film, “Amu” to tackle the Delhi “riots” — and alluded, as much as they could, to it being congress-lead — in a form palatable to non-Punjabis. And documentary film maker, Harpreet Kaur, who made the “Widow Colony” and most recently, “A Little Revolution,”a documentary about the children of farmers who committed suicides (both films are highly recommended and extremely powerful).

These artists obviously have ties to Punjab in some capacity, but none of these artists live in Punjab, and while their stories are a valuable part of the conversation, the conversation is incomplete without the Punjabi voice from Punjab. Where is it? Not every youth in Punjab is addicted to drugs. And there are plenty that recover from their addiction, and return to the world of bleak futures and temptation to alcohol and drugs at every corner. Perhaps this is where we should be spending more of our time and energy, rather than protesting Bollywood films, or buying that gold karra. Without taking logistics into account (yes, I know it’s kindof a big deal), encouraging a people who love to tell stories and express themselves musically, visually, and through written word, is not difficult.

Who knows – maybe the next Bollywood screenwriter and director will be a sardar from Amritsar, or a former drug addict will pen the next great Indian novel or a Punjabi poetry collection. Or a Punjabi rapper from Punjab will emerge, one who is actually grounded in the history of hip-hop, rather than continuing the trend of hip-pop with girls outnumbering guys at “parties,” plenty of alcohol, and catchy, but vacuous lyrics pervading the genre today. Perhaps, the next Jagjit Singh will have the confidence to take on the world of the ghazal and not be afraid of keeping his Sikh appearance.

Who knows – maybe the next Bollywood screenwriter and director will be a sardar from Amritsar, or a former drug addict will pen the next great Indian novel or a Punjabi poetry collection. Or a Punjabi rapper from Punjab will emerge, one who is actually grounded in the history of hip-hop, rather than continuing the trend of hip-pop with girls outnumbering guys at “parties,” plenty of alcohol, and catchy, but vacuous lyrics pervading the genre today. Perhaps, the next Jagjit Singh will have the confidence to take on the world of the ghazal and not be afraid of keeping his Sikh appearance.

I leave you with a poem by revolutionary poet, Habib Jalib. “Jaag Mere Punjab,” which will hopefully reverberate, even decades after he first wrote it, and will transcend East and West Punjab politics, and simply address the issue of Punjab as a whole. And hopefully, we stop being satisfied with the adage, “yeh India/Pakistan hai. Yahan sab kuch chalta hai” and start asking questions inwardly to incite a real change, as small as it may be on how to solve some of the issues that affect Punjab.

Note: “Chala” in the context of this poem means “to ebb” and “Pakistan” represents “an authoritative regime interested in assimilating all subcultures and languages.”

Here is the original version of the poem:

Here is an homage to Habib Jalib’s original, by the Laal Band (this has better audio, but no translation):