'To me the place seemed like a dream/ And far ran a lonesome stream.'

The lines are from a poem written by an English artilleryman as he beheld a beauteous scene in the western extremities of the British Raj. The place had occupied, preoccupied, British minds before. In Mughal times, the 'place like a dream' had been home to mixed tribes that soon began to assert independence from the powers at Agra and Delhi. Chaos spells opportunity for the daring. Maharaja Ranjit Singh, using his Zam Zam gun and his cavalry, established hegemony over the Frontier tracts, his empire thereby acquiring much of what today is Pakistan, Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir and Jammu and Kashmir. But when has seized territory stayed in the seizing clasp?

The British followed opportunity when they saw it, calling it danger one day, self-interest another. And when Ranjit Singh, crippled by two paralytic strokes, was on a low tide, they used him deftly to checkmate Russia in the Great Game.

Our young artilleryman, the author of that rather schoolboy poem, had joined the Bengal Artillery at the age of 16. Deployed to play a role in a diplomatic manoeuvre of the Great Game at Khiva in 1839, he volunteered for action in the aftermath of the popular revolt that gathered momentum against Sikh rule. Sikh nationalism had to - and did - retaliate. Violating the Treaty of Lahore, it threatened the loose sway that Britain had established for itself west of the Sutlej. Governor General Dalhousie, just six months into his office, declared, in October 1848, "Unwarned by precedent, uninfluenced by example, the Sikh nation has called for war, and on my words, Sirs, they shall have it with a vengeance."

The soldier-poet was among those destined to be noticed and deployed for that bloody but decisive war. By March 1849, after pitched battles, including the celebrated one at Chillianwala, the Sikh army surrendered and Punjab was annexed outright. A report sent to the board of the East India Company put it graphically: "... a difficult frontier has been guarded, 500 miles long, inhabited by a semi-barbarous population and menaced by numerous tribes of hostile mountaineers... With a police force of 14,000 men, internal peace has been kept from the borders of Sind to the foot of the Himalaya, from the banks of the Sutlej to the banks of the Indus..."

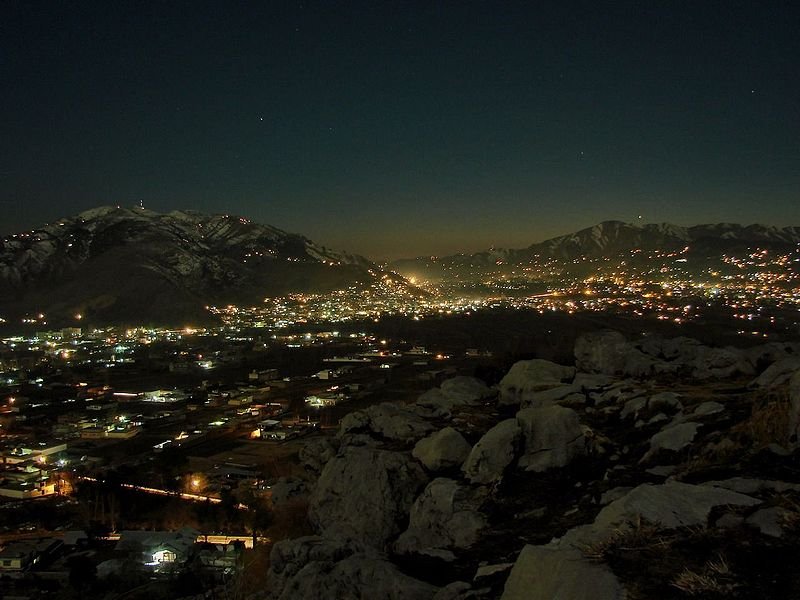

Hazara was among the areas where peace had been brought. It was described as "... a wedge of territory extending far into the heart of the outer Himalayas, and consisting of a long narrow valley, shut in on both sides by lofty mountains, whose peaks rise to a height of 17,000 ft above sea level [it] is bounded by mountain chains, which sweep southward... and send off spurs on every side which divide the country into numerous minor dales... well watered by the tributaries of the Indus, the Kunhar, which flows through the Kagan Valley into the Jhelum, and many rivulets..."

The artilleryman, now well experienced in both war and pacification, was appointed Hazara's first deputy commissioner. His name: James Abbott.

Scouring Hazara, Abbott held his breath as he saw these beauteous hills with streams around them. Picking one such spot, some 4,000 feet above sea level, he decided he would set up a new hill station there, a westerly Darjeeling. Abbottabad, it came to be called. But when has seized territory...

Less than a 100 years after Abbott had encountered those regions, the British Raj was in retreat, World War 2 was about to break out and a 'tribal' leader, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, did the unimaginable. He started a movement of the Khudai Khidmatgar, which, in Pashto meant 'Servants of God', for a non-violent Pashtuni struggle against the British Raj in an Islamic context and vocabulary.

What would have also stumped the British even more is that Ghaffar Khan, known also Badshah Khan, motivated his cadres, the 'Surkh Posh' (Red Shirts), to work for the elimination of blood feuds. And, wonder of wonders, on more than one occasion when Hindus and Sikhs were attacked in Peshawar, the Red Shirts helped protect their lives and property. "There is nothing surprising," said Badshah Khan, "in a Muslim or a Pathan like me subscribing to the creed of non-violence. It's not a new creed. It was followed 1,400 years ago by the Prophet all the time he was in Mecca."

Not surprisingly, he was rebuffed by the Muslim League. Along with his brother Khan Sahib, Badshah Khan gravitated towards Gandhi. The two brought meaning to the term 'kindred spirits'. The Khudai Khidmatgar gave Gandhi a hope and a vigour he, too, could never have imagined.

Visiting Abbottabad in 1938, Gandhi inhaled its pure air and also drew on its history of turbulence. He wrote to Madeleine Slade from Abbottabad: "This is a beautiful place except for its associations." Back in Abbottabad the following year, he stayed there for over 10 days, the Khidmatgars looking after him as they would an elder from within their own kin. And they gave him time for thinking of issues beyond that province - among which was the phenomenon, then 50 years old, and rearing its head, called Adolf Hitler.

The ogre-in-the-making had already entered Vienna and Prague and was contemplating the invasion of Poland when Gandhi wrote to him, from Abbottabad, on July 23, 1939: "Dear friend, friends have been urging me to write to you for the sake of humanity. But I have resisted their request, because of the feeling that any letter from me would be an impertinence. Something tells me that I must not calculate and that I must make my appeal for whatever it may be worth. It is quite clear that you are today the one person in the world who can prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state. Must you pay that price for an object however worthy it may appear to you to be? Will you listen to the appeal of one who has deliberately shunned the method of war not without considerable success? Anyway I anticipate your forgiveness, if I have erred in writing to you."

The diabolism of the period between 1939 and 1945, which saw 11-14 million people, including about 6 million Jews, killed in concentration camps and ghettoes lay in the wordless future. As did deaths through "less systematic methods" as a result of starvation and disease. That an Indian voice had challenged "for the sake of humanity" a new and unimaginable menace to human civilisation before that menace had bared all its fangs, to "prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state" is not sufficiently known. That the challenge was made from Abbottabad , can't now afford to remain unknown.

So have we exorcised the ogre of a savage state? The most formidable and the ferocious are yet the most vulnerable. Be they be ever so well-bunkered in a metropolitan residence or in a 'place like a dream' not far from where beckons... a lonesome stream.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi is a former administrator, diplomat and governor.

The views expressed by the author are personal.