These ruins speak of the multi-faceted identity of the city, where many religious cultures once flourished.

Sep 20, 2015: In the heart of Lahore, where the ancient city merges with the burgeoning metropolis, where the upper-class localities interact with the lower-class localities, lies the shrine of a Sufi saint called Shahjamal.

Situated on the top of a mound, the shrine overlooks the city’s different identities -- the ancient locality of Ichra; Forman Christian College, the first English-medium institute of Lahore; the Lahore Jail, where Bhagat Singh was incarcerated and later hanged; Muslim town, a suburban residential scheme set up by a man from the Ahmadiyya, a sect that was subsequently declared non-Muslim in Pakistan.

Every Thursday, the holy day in Islamic Sufi tradition, mystics gather at the courtyard of the shrine to perform the dhamal, a devotional dance that involves a frenzied and ecstatic swirling of the head and the body. Anthropologist Jürgen Wasim Frembgen believes that the dhamal in the Indo-Pakistani context may have been influenced by the tandava dance of Shiva, a furious violent dance that has the potential to destroy everything in its way.

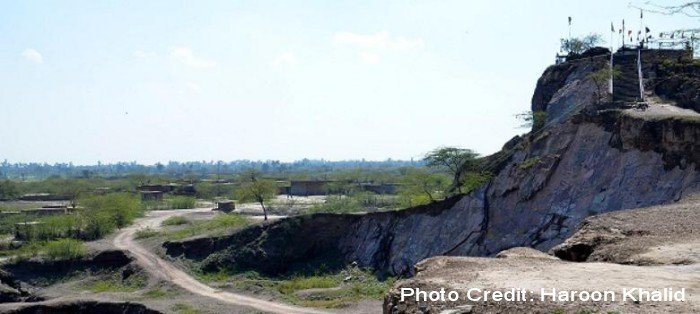

An archaeological mound close to the shrine of Shahjamal. Photo: Haroon Khalid

It was on top of this mound that the Sufi saint Shahjamal used to reside in the early 17th century. According to a folk legend, his mound used to overlook the palace of a Mughal princess, who felt that her privacy was invaded by the saint. The princess complained and when Shahjamal heard about it he started dancing the tandava passionately, resulting in the destruction of the palace, which got buried under his foot. The palace became a mound of ruins and the saint continued living on the top of it.

The shrine today is a vast complex of marble and concrete. Like most of the other religious shrines it too was constructed over several generations as donations from devotees poured in. Before the earth of the mound was covered by concrete, remains of pottery, bricks and may be even bones were found there, giving birth to this story of the miracle about the palace. There are, therefore, strong reasons to believe that this was an archaeological ruin that the saint did use as an abode, given that it was isolated from the city.

Historians believe that the original city of Lahore was not the current walled city but the locality of Ichra, facing the shrine of Shahjamal. Buried underneath his shrine is the secret to this mystery. However, before the science of archaeology arrived on the Indian sub-continent via the British, this mound had already been converted into a shrine, perhaps forever becoming inaccessible to archaeologists.

There seems to be a peculiar relation between Sufi shrines and archaeological mounds. About 100 km from Lahore is Shahkot, a small town. At the centre of this town is the shrine of Baba Naulakh Hazari. One of the greatest miracles associated with the saint is the story of his pet lion and lamp. It is said that living under his influence, the lion and the lamp started drinking water from the same pot.

The shrine of Baba Naulakh in the background. Photo: Haroon Khalid

Like Shahjamal, Naulakha Hazari, too, chose to settle on top of a mound away from the city. He was eventually buried in the city, while a modest shrine was constructed at the mound where he is believed to have spent his time in meditation. Climbing the steep mound I noticed several layers of civilisations buried within. Archaeological records state that this city was burnt down by the forces of Alexander the Macedonian. I did notice a layer of charcoal within the mound, perhaps from that time.

Ruins of a burnt village. Photos: Haroon Khalid

In one place, there was a heap of bricks, also remnants of an ancient civilisation. Noticing my interest, two local boys claimed that they had discovered other ancient artefacts from here. At the top of the mound was the rock with a niche from where the lion and the lamb were once supposed to have drunk water together. Next to it were other rocks with fossils of pre-historic flora and fauna. They had now become an object of veneration at the shrine.

Like the mound of Shahjamal, this one as well will also probably never be dug up, but not because it is a religious shrine but because it has now been bought by a new housing scheme, which has slowly eaten away into it to make way for wide roads and big plots for a quintessential suburban locality.

Muslim Sufi shrines are not the only religious shrines that were constructed over mounds. At a village called Jhaman, on the outskirts of Lahore, is the historical gurdwara of Guru Nanak. It is believed that Guru Nanak visited this village while he was visiting his maternal house. He chose to stay on a mound outside Jhaman.

The name of the shrine eventually became Rori Sahib, rori being the Punjabi word for shards of pottery found on this mound. They testify that buried underneath the shrine is an archaeological mound. According to archaeological survey reports, this mound maybe as old as the sixth century CE.

Gurdwara Rori Sahib. Photo Haroon Khalid

Religious shrines emerged at the mounds of Taxila and Harappa and continue to thrive after they were unearthed by the British. But while archaeologists were able to continue working in Taxila and Harappa, other mounds became pilgrimages or shrines and could not be studied.

A Sufi shrine at an archaeological site in Taxila. Photo Haroon Khalid

The Indus Valley civilisation was one of the last ancient civilisations to be discovered, and today we know the least about this civilisation of all ancient civilisations, primarily because these mounds were re-appropriated into the subsequent civilisations that emerged here.

On the one hand, this integration of archaeological mounds within the life of cities and villages is bad news for archaeology, hindering its progress. On the other hand, it reflects a vibrancy of the culture and civilisation, which re-appropriates even an abandoned mound into its fold. It is through this process that a mound or ancient symbols become sacred objects or religions shrines, very much part of the community of that area.

In a lot of cases myths and legends about these ruins become part of the folklore, and acknowledge their antiquity. For example, much before the British discovered the ruins of Taxila, there were legends in the local community about an ancient mound of kings.

Haroon Khalid is the author of A White Trail and two forthcoming books, In Search of Shiva and Walking with Nanak.