(This article is the first in a series from our newest SikhNet contributor, Sarbpreet Singh. It has been adapted from the script of The Story Of The Sikhs, a Sikh History podcast that he recently launched.)

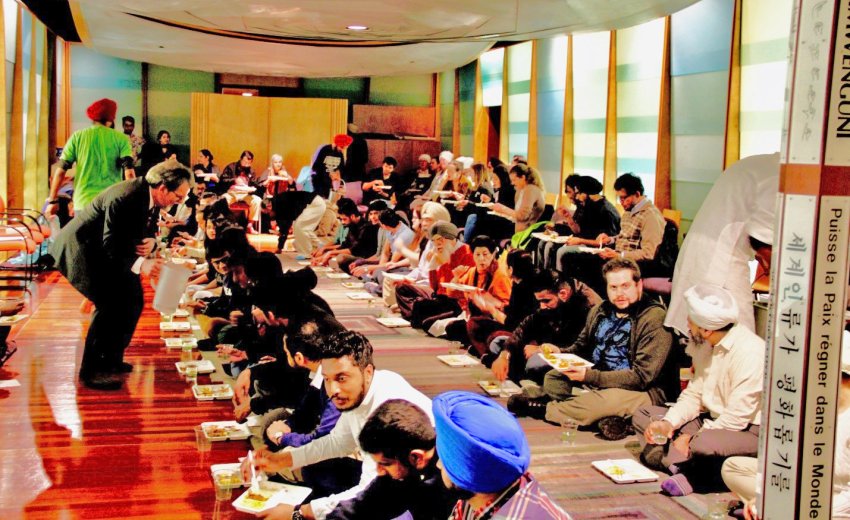

In the summer of 2004, a few yards from the glittering waters of the Mediterranean, stood a gigantic steel framed tent. Eight thousand men, women and children from all over the world had gathered in Barcelona for the Parliament of the World’s Religions, the world's largest interfaith event that occurs every four to five years. Some of the most joyous and meaningful memories the attendees took back with them were of the meals that they were offered in the tent, three times a day, prepared and served by Sikh volunteers from the UK. For many, it was their first experience of the Guru Ka Langar or the communal Sikh kitchen, established by a young man whose obdurate opposition to all occupations worldly had driven his parents to distraction five hundred years earlier.

The story goes that one day, the young Nanak, as usual, was sitting idle at home when Mehta Kalu stormed in and started to berate his son. Nanak begged forgiveness and promised his father that from that moment on, he would be the most obedient of sons. Mehta Kalu bade him to go to a nearby town to buy salt, turmeric and other items, which were then to be sold at a profit to launch Nanak’s career as a trader. Mehta Kalu handed twenty rupees to a servant that he commanded to accompany Nanak on his mission and sternly remonstrated with him to ensure that he struck a good bargain. Determined to carry out his father’s wishes, Nanak, with his companion set out for the town. Mehta Kalu, familiar with his son’s ways, accompanied them part of the way, reiterating the high expectations he had of his son ever since his birth and how important it was to him that he be successful, become a credit to the family and increase its renown. Finally he let them proceed on their own and and stood rooted to the spot, watching his son’s figure receding in the distance with fondness.

After they had walked for a bit, they came upon a forest which was home to a gaggle of holy men of every imaginable stripe. Nanak paused, taking in the wondrous scene, his eyes shining. Some of the holy men were seated silently and calmly, eyes shut in deep meditation. Some were performing austerities, twisting their bodies in complicated postures or standing upright with their arms stretched to the heavens. Others sat warming their hands around smoking mounds of twigs and leaves and some sat in the lotus position. A solitary man sat naked in a small pool of water. All of them had sacrificed worldly comforts in their quest for the glories of the afterlife. Some had taken a vow of silence. Their leader was seated on a deerskin, spread out under a tree, lost in his reflections on the divine as one of his followers carefully perused ancient texts by his side.

Nanak whispered to his companion excitedly. What better bargain could there possibly be! Let us make an offering of the money to these fine holy men. They will eat and buy clothes and they will be pleased! His companion, in great alarm voiced his disagreement. Your father, Mehta Kalu gave you strict instructions to buy goods for trading with the money and you know his temper! But I am your servant and I shall do as you say. With this he handed the money to Nanak, who approached the leader of the holy men, saluted him politely and squatted on the ground before him. He looked at the naked holy man with his body coated with ash, in wonderment and asked. You wear no clothes on your body at all! The heat, the rain, the cold it must cause you a lot of discomfort! Upon which the holy man, eyes flashing with anger retorted that it was not Nanak’s place to ask.

Perhaps fearing the holy man might curse his master, Nanak’s companion pleaded with him to get up and leave so that they could complete the task that Mehta Kalu had assigned to them. But Nanak dug in his heels and declared that a better bargain was not to be had anywhere else. Nanak, unafraid of the holy man, addressed him again. If you don’t wear clothes, do you not eat as well, he asked curiously. The sage replied that he and his band ate whatever God sent them. They had renounced the world and had embraced the forest after giving up the comfort of their homes. Nanak smilingly turned to his companion and declared. See! I told you. A better bargain is not to be found and to the mutterings of dire consequences of his companion, placed the twenty rupees before the sage. The holy man refused the money but permitted Nanak to go to a nearby village to buy food for his fellow mendicants, which they ate with great relish as Nanak watched with a smile, ignoring his companion’s apprehension at what lay ahead. The holy men blessed Nanak, declaring that they had been hungry for seven whole days and dismissed him. Nanak humbly bowed before the holy men and took his leave.

As they walked back, Nanak’s sense of euphoria began to fade and he turned to his companion. What have we done! As they approached the village of Talwandi, Nanak, fearful of his father’s wrath, did not enter the village and disconsolately sat down under a tree at the outskirts. Mehta Kalu saw that Nanak’s companion had returned without his son and it didn't take long for him to drag the truth out of the terrified servant. Roaring with anger, Mehta Kalu stormed out of his house to look for his wayward son. His wife, Tripta, fearful of his anger, sent Nanak’s sister Nanaki in the hope that she might restrain her angry husband. Mehta Kalu found Nanak cowering at the outskirts of the village and asked him to explain his actions, after which he slapped him hard on both cheeks. Just then Nanaki arrived and feel at her father’s feet begging forgiveness for her brother, pointing to his cheeks, wet with tears, that had purple welts on them.

And thus, so it seemed, ended Nanak’s great bargain!

But the story didn't end there! From the ashes of Nanak’s failure as a merchant rose a great institution. One that was to reflect the ethos of the faith that the young man would go on to found. An institution that was to become the embodiment of the fundamental principles that Nanak and his followers were to live by. For this was the genesis of the Langar, The Sikh Community Kitchen.

For many in the West in particular, their most memorable experience of Sikhism and Sikhs is a visit to the Langar. It is always a convivial experience. Delicious food, served with a smile to anyone who visits a Gurdwara or Sikh place of worship or attends a Sikh religious service. But it is so much more than a communal meal. It is the legacy of Nanak’s great bargain and it is a living testament to Nanak’s rejection of the terrible injustice of the caste system and his embrace of social justice.

In the affluent West, a free meal at a community kitchen at a Gurdwara may seem to be interesting but hardly revolutionary, but it is important to view the Langar in the Indian context, where most Sikhs live and most Gurdwaras are located. It is also important to understand that the Langar is funded entirely through voluntary contributions. Despite all of its advances in the past few decades and a burgeoning middle class, India remains a poverty ridden country with mind boggling social inequality where hunger is an issue even today. Wherever there is a SIkh Gurdwara, the hungry are welcome to eat in the Langar three times a day, three hundred and sixty five days a year, with no questions asked! It is a powerful and lasting commitment to social justice, which was a fundamental part of Nanak’s creed. Nanak’s great bargain carried a powerful social message, which was not apparent to Mehta Kalu when he raised his hand to strike his son in frustration. Where he saw profligacy, his son clearly saw that there was no nobler or more meaningful use of one’s resources than feeding the hungry.

The second aspect of the institution that came out of the great bargain was no less significant. Even as a child, Nanak had rejected the sacred thread and the perpetuation of caste discrimination that it signified. Years after his rejection of the sacred thread and his great bargain, he instituted the Langar and in an act of sheer genius turned it into a practical tool for dismantling the evil of caste based oppression.

Commensality refers to the beliefs, practices, rules and regulations that determine inter-caste relationships regarding eating and drinking. Sociologist Adrian Meyer in his work : Caste and Kinship in Central India, writes about caste status through commensality :

The commensal hierarchy is based on the theory that each caste has a certain quality of ritual purity which is lessened or polluted by certain commensal contacts with castes having an inferior quality. Commensal contacts include the cooking of food and its consumption. A superior caste will not eat from the cooking vessels nor the hands of a caste which it regards as inferior, nor will its members sit next to the inferior people in the same unbroken line (pangat) when eating.

Anyone who has ever eaten at the Langar will immediately understand the significance of what Nanak did five hundred years ago! In the Langar everyone sits in an unbroken line, known as the Pangat and eats together. Today, it may not seem remarkable but five hundred years ago when caste distinctions were diligently and brutally enforced, this was revolutionary! Guru Nanak was clearly attempting to subvert an insidious, inhuman, social norm. Once Guru Nanak and his faith became well known, supplicants and devotees from every faith and station would flock to his congregation or Sangat, but none would be admitted to the Sangat until they had partaken of the humble fare of the Pangat, where they would eat with people of all casts and creeds, very publicly rejecting the fastidious rules of commensality.

The creation of the Langar and the Pangat by Guru Nanak was a compassionate and breathtakingly bold act of defiance. And its seed was that chance encounter with the holy men that earned the young Nanak a thrashing!

Read an Excerpt Episode Two - The Wanderers