|

| Thathera craftsmen at their native Jandiala Guru town near Amritsar. photo: vishal kumar |

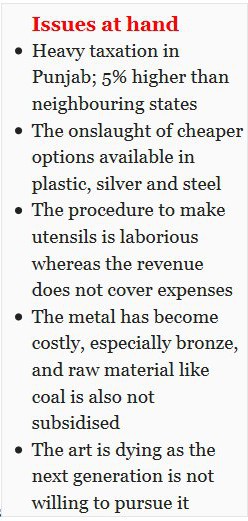

Their hands bear the onslaught of the changed times and their talent, gradually heading towards a slow death. The Thathera community of Jandiala Guru, famous for the craft of making copper, brass and bronze utensils, has made it into UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List, but the craftsmen hope for a miracle to revive the lost glory of the traditional craft.

Thathera craft dates back to the Mughal Era, and later pursued by the craftsmen, who settled in Jandiala post-Partition.

Thathera craft dates back to the Mughal Era, and later pursued by the craftsmen, who settled in Jandiala post-Partition.

Beating and crafting the metal for centuries now, the Thathera community today is reeling under the pressure of competitive market and abandonment by the establishment.

“Jandiala was once the biggest market of handmade brass utensils, even bigger than Moradabad and supplied to Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan. Over 500 families were involved in the business and there were 15 rolling machines, including five in Jandiala, six in Batala, two each in Phagwara and Hoshiarpur, for the purpose of manufacturing utensils. Today, only 1 per cent of the business remains with 20 odd families still into making utensils, and a single machine left for rolling,” informs Ajit Singh Malhotra, president of the Jandiala Utensil Manufacturers Association.

Malhotra’s family migrated from Gujranwala, like many other Thathera families, and set up shop at Jandiala. “The traditional utensils were gifted as dowry while marrying a girl as they were beautifully crafted. The pots, ‘thalis’, ‘gaggars’ (jug) and the unique ‘deg tamba’ (large traditional boiling copper pot), still used in gurdwaras for cooking, are unique to the community,” he adds.

Molten metal rolls are flattened into thin plates and then hammered and curved into utensils, under careful controlled temperatures with the aid of wood-fired stoves. The hammering of dents provides the designing for the utensils, which are polished by acid treatment or using tamarind.

The cost of manufacturing these utensils comes out to be approximately Rs 400 per kg. Even the few craftsman making ‘deg tamba’ are being paid daily wages of anything between Rs 20-40 while the market selling price of the product is somewhere between Rs 500-540. “The retailers eat a major share of the profits and we are left with nothing, but meagre amount to carry on our lives with,” says one of the craftsman.

The onslaught of cheaper options available in plastic, silver and steel has cut down the business considerably as the demand has dried up.

Harvinder Singh Malhotra, another craftsman, says the procedure of making utensils is detailed and laborious and the profit margins do not cover the expenses. “The metal has become costly, especially bronze, and raw material like coal is also not subsidised. On top of that, one has to devote eight to 10 hours into the manufacturing process, which includes melting and hammering the metal. The art is dying as the next generation is not willing to pursue it,” he says.

Another major reason for the slow death of the Thatheras’s craft is heavy taxation. “The manufacturing and freight tax on the product and unfavourable government policies have deeply affected the business. Haryana and Rajasthan have 2 per cent tax on utensil manufacturing while here it is 6-7 per cent. Also, most of the manufacturing units have shifted to Himachal as they have subsidised land rates. Also, the government aid and funding is negligible. The sad truth is that some of the exporters and retailers buy scrap from us and sell it at exorbitant prices in overseas market in the name of heritage and antique art even as the real craftsman and heritage is waiting to be rescued,” says Ajit Singh.