Dallas, Brussels and Guadalajara are the finalists to host the 2014 Parliament of the World's Religions. If Dallas is chosen to host the meeting, what themes would you suggest the international forum focus on?

Dallas, Brussels and Guadalajara are the finalists to host the 2014 Parliament of the World's Religions. If Dallas is chosen to host the meeting, what themes would you suggest the international forum focus on?

This question seems pertinent to our weekly discussion because we have concentrated the last few months on how to create a genuine religious dialogue. By genuine, I mean one where differences are acknowledged, debated and understood, not treated as if they don't exist.

The question also gives you a chance to step back and envision what issues may be most challenging to the world in another four years. Journalists are very good at looking backward, but I would love to hear from each of you what themes you think we are likely to be dealing with in another four years.

AMY MARTIN, Executive Director, Earth Rhythms; Writer/editor, Moonlady Media

The Parliament of the World's Religions is a phenomenal grass-roots movement. If the parliament is hosted here, and there is an excellent chance of that, it will be more than a huge religious gathering of over 6,000 people from dozens of religions and faith paths from around the globe.

During the two years preceding the parliament, the host committee is charged with making contact with every church, synagogue, temple, coven and other faith grouping in North Texas. Weaving such a tapestry of religious community while broadening perceptions of our diversity can only strengthen our region.

More than that, the parliament looks at ways its presence can help its host community move forward on persistent problems. The local parliament committee identified the economic and environmental disparity between North Dallas and the south and west parts of Dallas as the city's greatest challenge.

In four years, environmental economics will be at the forefront. Living sustainably is increasingly seen as a moral issue, as is allowing underdeveloped countries and the poor to bear the brunt of manufacturing pollution. Access to clear air and water and untainted food is also increasingly seen as more moral than political.

However, judging by the extensive survey by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, the most pressing issue faced by established religion itself are the fast rising numbers of those who claim no religion at all, though many maintain an active spiritual life. Now comprising 16% of the general population, among those below 30 years of age it is over 30%.

How will this meteoric rise of the agnostic/spiritual not religious/unaffiliated impact society? How will churches and other spiritual centers adapt? If this trend reduces their number, what will source the vital community and charitable works they previously provided? Without sanctioned leaders, how will the agnostic/spiritual not religious/unaffiliated make their voices known?

Religion reaches into the core of who we are as humans, it urges us to evaluate what is truly important in our short times here on Earth. The Parliament of the World's Religions provides an isthmus between the myriad faith paths, a safe and common ground for us to stand in peace and discover our highest common denominators.

LARRY BETHUNE, Senior Pastor, University Baptist Church, Austin

I would like to see more honest and direct dialogue about violence at the Parliament of World Religions, including especially violence in the name of religion. While most religions prize peace and reject violence as a means of achieving spiritual goals, most have also betrayed those values at different points in their history by perpetrating violence in the name of the Divine for purposes of expansion, conquering enemies, and internal control.

Such violence includes not only direct physical damage, but the violent language and attempts at coercion and control that precede physical aggression. Exploring the connection between violent language and violent action might lead to a deeper understanding of what global peace requires.

The problem of religiously inspired violence is not new, of course, but it is increasingly dangerous. Religion is often exploited illegitimately by political forces as a motivation for violence, and the mainstream leaders of those religions disassociate themselves from extremists who betray their core values.

But extremists usually justify their behavior by appeal to some genuine part of their theology or tradition. Extremists may pathologize their religion, but they are inspired by, appeal to, or are empowered by some original abiding element of their faith. Therefore, each religion needs to examine its core tradition for ways in which violence is legitimized and even intrinsic to its theology.

Lest one religion be labeled as more violent than others (Islam, for instance, in the current climate), every religion needs to review its history and theology for an honest assessment of its divinization of violence. A mutual dialogue based on honest self-assessment could lead to new ways of avoiding, rejecting, and renouncing violence as a means of achieving religious goals.

There are many other worthy topics the Parliament of World religions might consider, such as "Children in Poverty," "Stewardship of the Environment," and "Defining and Defending Human Rights," finding a solution to religiously sponsored violence creates the space to address all of these.

GEORGE MASON, Senior Pastor, Wilshire Baptist Church, Dallas

We have been concentrating on the question of how to live respectfully with one another by acknowledging our religious differences and not pretending that every religion is fundamentally the same, thus minimizing the particular truth claims made by each.

But we also need to acknowledge that one common value or teaching in all our traditions is some version of the Golden Rule -- "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." If the truth claims of any religion are ever to be taken seriously by outsiders, it will only be because the door of inquiry has been opened by a bold and consistent witness to the ethical principle of the Golden Rule.

Conflicts throughout the world today reveal an inability to transcend history. Stories of injustice across centuries continue to fuel a passion for redress, if not revenge. Religion offers the only viable way to break the cycle of violence that keeps us from moving on constructively together. Every religion has to be honest about how it has helped to foster violence in the name of God instead of being a force for peace with justice that alone honors the name of God.

True human flourishing is never achieved on a lasting basis as a zero sum game -- one in which there is only enough dignity and prosperity for one of us, you or me, which makes me always strive for mine at your expense. Religion must insist that there is enough to go around for everyone at the same time and that hospitality and generosity toward others is not a luxury we practice when we are in a position of power to do so; it is a spiritual necessity that either validates or invalidates our religion.

KATIE SHERROD, Progressive Episcopalian activist, independent writer/film producer, Fort Worth

Wherever this conference is held, I hope it will address an issue of vital, even life and death importance to more than half of all humanity, and that is "Are women created in the image of God?"

This question is THE core question, because out of it arises issues of education, poverty, violence, access to medical care, the spread of AIDS, the treatment of indigenous people, infant mortality, even peace and justice.

If the answer is "Yes, women are created in the image of God," then what does that mean to those religions that insist on treating women as somehow less human than men? To take a current instance, what does it say about the Roman Catholic Church's recent equating of those who ordain women with those who rape children?

If the answer is "no", what does that say?

It is not too strong a statement to say that religions have been and remain the largest means of oppression of girls and women in the history of the world. As the theologian Mary Daly famously wrote, "Once God is male, then the male is god."

Once you can use God to justify misogyny you can justify many other oppressions. It becomes easy, even necessary, for those privileged men in positions of power to start adding to the list of those who are less worthy -- people of color, disabled people, indigenous people, even poor people. And, of course, that most stable scapegoat of all _-- gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans-gendered people.

But I suspect this conference, like most religious conferences, will talk more about the issues that emanate from this core question than they will the question itself. It's too threatening to patriarchal privilege to do otherwise.

WILLIAM LAWRENCE, Dean and Professor of American Church History, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University

The Parliament of the World's Religions has offered a fascinating forum for interfaith conversation, according to one faculty member at Perkins School of Theology who has attended the last two parliaments. Dallas would be blessed to host such a significant international event.

My thematic suggestion is "The Languages of Religious Life." By 2014, if we have not either killed one another or become captives of some tyranny for the sheer sake of survival, human beings may be ready to take a fresh look at the resources of religion for a way to live. One of those resources is a capacity for creating community where there is no obvious advantage to doing so. We could discover that the languages that we use internally within our own religious sects have common ground in other faith groups.

First, there is the language of silence. From Quakers and contemplatives in Christianity to Buddhist practices, one of the very basic languages is the form of speech that avoids using words. The adherents of religious approaches based on silence could establish lines of communication with one another AND they could invite those of us in other groups who depend upon the "word" to listen to them.

Second, there is the language of domination. Both Christianity and Islam, for example, can point to sacred texts -- or at least to the common interpretations of those sacred texts -- within their traditions that emphasize their access to the "truth" and their responsibility for delivering that truth to the rest of the world by whatever means possible.

Both have shown their willingness to create systems of delivery, such as through Crusades, that are prepared to crush and conquer any alternatives to their own understanding of truth. Advocates of such systems may be the least likely persons to register for a Parliament of the World's Religions, but if such a parliament does not permit itself to encounter such voices it will have ignored a large segment of the world's faiths.

Third, there is the language of social order. Here is the place where Dallas may be a particular fine location for the meeting.

On the one hand, people in North Texas live in a political context that values the rights that are constitutionally secured, including the assurance that Congress will make no law respecting the establishment of religion nor prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

On the other hand, people in North Texas also live in a political context that grants exceptional privileges to something often described as our Judeo-Christian heritage. To my knowledge, there were among the founding fathers who signed the Declaration of Independence no Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, or (for that matter) Jews.

They could have specified a preference for some religious perspective over others, but they did not -- either in the Declaration or the Constitution. Nevertheless, the social fabric in the United States has been woven with threads that both build a wall of separation around religion and make the wall porous. Can a Parliament of the World's Religions have conversation about the "languages of religious life" that are ambiguous with regard to the social order?

Let's hope so. If we are still here in 2014, we will need to talk about that.

DARRELL BOCK, Research Professor of New Testament Studies, Dallas Theological Seminary

Three or four issues stand out. Cooperation in dealing with violence, hunger, poverty and the care of global resources would be on my list. I would hope a universal statement could be issued decrying any form of religious persecution that kills, harms or destroys property.

MATTHEW WILSON, Associate Professor of Political Science, Southern Methodist University

One major theme that would be appropriate in any venue, but especially in Dallas, would be the moral issues surrounding migration.

All of the nations of the developed world are likely to face heavy flows of incoming migrants from poorer countries in years to come, and these new arrivals will face both cultural and economic backlash. Rather than simply dismissing or condemning those who are troubled by large-scale immigration, the world's religions would be well advised to engage thoughtfully the economic, cultural, and security implications of human migration, and to develop a framework for moral response.

Is there in fact an inherent right to migrate? Can states legitimately limit the terms of migration? If migrants violate any such limits, what are the bounds of morally permissible state response? Is there any legitimate moral basis for laws intended to promote common language, culture, and values within a nation? These questions strike me as pressing ones in an era of mass migration, and they are issues are ripe for inter-faith and inter-cultural dialogue.

Another issue that I would like to see the Parliament of the World's Religions address is the issue of proselytism. Various religious groups around the world seem to take umbrage when those of other faiths seek to convert their members.

Catholics in Latin America resent evangelical proselytism, evangelicals in America resent Mormon proselytism, Jews resent Baptist proselytism, Muslims in the Middle East resent (and often prohibit) Christian proselytism, Hindus in India resent (and often react violently to) both Muslim and Christian proselytism, and the Orthdox in Russia resent everyone's proselytism.

It would be very useful if the world's great religions could reach an understanding on this score, one that would embrace the individual's freedom of conscience and allow the respectful, non-coercive sharing of religious messages.

Members of evangelical faiths like Christianity, Islam, and Mormonism cannot be true to their own religions without sharing the message with others--and that sharing will, at times, produce conversions. This can be difficult for non-evangelical faiths, like Judaism and Hinduism, to accept, and even the evangelical faiths do not always extend to proselytizers of other creeds the same openness that they would ask for their own.

Dialogue on this issue at the upcoming Parliament would be most welcome.

CYNTHIA RIGBY, W.C. Brown Professor of Theology, Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary

Here are four of the issues I believe will have come to a head, four years from now, and will need to be addressed at the parliament:

Global capitalism and poverty. My guess is that the global economy, in four years, will be moving toward recovery from the recession, and that we will be picking up steam again re: spending more than we have.

The rise of global capitalism clashes with the mandates of many world religions to share with/provide for the poor. The problem might not be with capitalism, per se, but with the rampant consumerism that has taken captive our value systems and widened the gap between the rich and everyone else.

What do the world's religions want to say to address economic disparity? Time and energy should be devoted, at the 2014 conference, to deep reflection on and analysis of economic realities, as people of faith.

Violence against women and children. As has been noted before on this blog, "The Elders" have been devoting significant energy to challenging leaders of different faiths to acknowledge and address the ways in which their traditions perpetuate violence against women. I commend these efforts, and hope that violence against women will be a theme at the 2014 conference.

In addition, I suggest that we address the related concern that violence against children, globally speaking, is on the rise. The fact that children are being used as soldiers, in various places in the world, is deeply troubling. Our faith traditions call us to stand up for the marginalized - what does this mean for how we advocate for women and children who are treated more as commodities to be used up than as human beings to be loved?

Technology and spirituality. In the next few years we will see a rise in the number of people, globally, who participate in worship services, seek pastoral care, engage in virtual rituals, and try to learn theology over the Internet. There will be some benefits to this, as there already are - for example, inexpensive access to resources; people of faith, from all over the world, joining (metaphorical) hands across cyberspace.

But there will continue also to be serious questions that emerge, such as: "is cyberspace spirituality a disembodied spirituality?" and: "if so, what do we lose, in our spirituality, when bodies are not literally, for example, breaking bread together?"

I know of one pastor already who preached a sermon titled: "Can my Avatar take Communion?" There will be a lot more sermons like this in the coming years.

Identity and Dialogue. How do we remain faithful to our particular faith traditions while at the same time remaining committed to listening to, and learning from, one another? How do we acknowledge both our differences and our similarities? How do we fight with each other productively, as people of faith? These questions are pressing now, and will continue to be pressing four years from now.

MIKE GHOUSE is a speaker on Pluralism and Islam and offers pluralistic solutions on issues of the day;

A frequent guest on the media. His work can be found in three websites and 22 blogs listed at www.MikeGhouse.net

The theme that might capture our imagination and encapsulate our issues in 2014 would be, “A legacy for the next generation” or “A legacy for seven generations.” It is not a new idea; it is a tradition of the native peoples of America.

The issues that affect our lives in the coming decade will continue to be environment, water, hunger, religious and ethnic intolerance. If we shy away from consciously shaping our future, we may drift into the abyss of incoherence. We may be fighting against deeply entrenched positions rather than finding solutions to the common issues.

Although the environmental future looks gloomy, the world is a better place today because of a good legacy bequeathed to humanity by people of all faiths that came before us. We owe it to the coming generations to leave the world a little better than we found it, to usher an era of justice and peace. Prophet Mohammad (pbuh) described a good deed as an act which benefits others, such as planting a tree that serves generations of wayfarers with fruit and the shade with a clear realization that we may not be the beneficiary.

A theme like, “A legacy for next generation” can also address the issues we consistently face. The social cohesion in particular and religious integrity in general continues to be challenged. The anti-Jewish, Gay/Lesbian, Catholic and Immigrant protest by Fred Phelps last week; the courts ordering to tear down the Sikh Gurudwara in Austin; the challenges against the planned Muslim center near ground Zero; the shootings at the Holocaust Museum in DC; the Arizona anti-immigrant laws; the rights of a woman to be a preacher and the resistance she faces to be the president and a host of other trends may scar the social fabric of our nation in the coming years. God has his own ways of repairing the world and the Parliament of Worlds Religions in 2014 may serve as a catalyst to a positive future.

“Sharing the planet together” is another viable theme. A dash of unselfishness is a necessity for all of us to feel safe and secure, it sails an individual or a nation through the good and bad seas fairly smoothly; indeed it is an insurance policy against the vulnerable moments of life.

God’s creation is intentionally diverse and each one of the seven billion of us has his own unique thumb print, DNA and a mind, and it is time we respect the diversity of thought and worship as well.

The pastors, pundits, imams, rabbis, shamans and other religious and spiritual leaders have a responsibility to bring about a new paradigm in our thinking; consciously creating “a legacy of pluralism” for the next generation.

The Council for a Parliament of the World's Religions was created to “cultivate harmony among the world's religious and spiritual communities and foster their engagement with the world and its guiding institutions in order to achieve a just, peaceful and sustainable world.”

A coalition of diverse community organizations is developing in the DFW Metroplex and is humbly seeking to be represented by every religious, social, ethnic, cultural and diverse landscape of our region.

| Desmond Tutu View Archbishop Tutu's special address to 2014 Parliament bid delegations more... |

|

| Sakena Yacoobi Courage Meets Compassion: the Council's exlcusive interview with Dr. Sakena Yacoobi. more... |

|

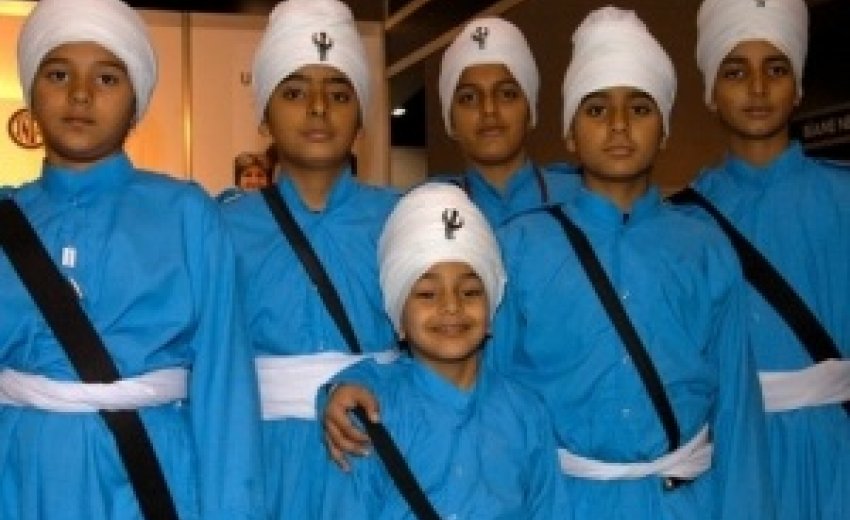

(Images are from the Parliament of World's Religions 2009 held in Melbourne.)

Story Contributed by:

Harbans Lal, PhD., D.Litt(hons)Emeritus Professor and Chair, Pharmacology & Neuroscience, U. North Texas Health Science Center