So much of our Sikh architectural heritage has been lost over the years.

I am amazed when I see photographs of churches and mosques and palaces over a thousand years old that are still intact. Here we are as Sikhs, the youngest major world religion, yet we have hardly any architecture over a hundred years old still standing.

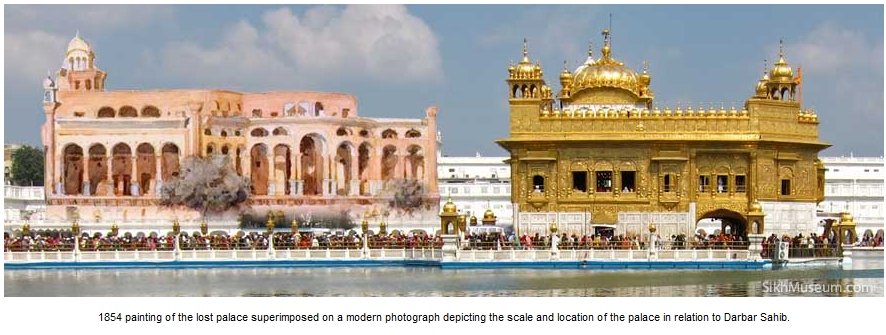

While researching artist August Schoefft’s epic painting of Maharaja Ranjit Singh at Darbar Sahib for a SikhMuseum.com exhibit, I became intrigued by an unusual structure appearing in the painting. It was a large and majestic palatial building on the parkarma of Darbar Sahib, with huge columns and spectacular arches, unlike anything I had ever seen before.

That initial curiosity about this unusual looking building started a quest that lasted years.

I then started specifically looking for this building in every old photograph or painting of Darbar Sahib and its surroundings that I could find.

Trying to find information about this mysterious building became a challenge, a journey of discovery. Why was it that one of the largest buildings on the parkarma ever built, a palace so large that it dwarfed every other structure on the periphery of the sarovar at Darbar Sahib and seemed to be even larger than the Akal Takht in volume, had simply disappeared from our records and collective memory?

What was this building? Who built it? What happened to it?

The lost palace haunted me like a ghostly figure clouded in mystery in the fog of time.

Research eventually revealed bits and pieces of this historical jigsaw puzzle. Old paintings, some of the earliest photographs ever taken of Darbar Sahib in the 1850’s and early traveller’s accounts, all revealed the remarkable story of the lost palace.

Like a time traveller I was able to take a journey of discovery from the time of the great Sikh Empire, to the advent of British rule in Punjab and the fascinating story of what happened to the lost palace and the strange and hideous structure built by the British to hurriedly replace it in the 19th century.

Visit the newly launched SikhMuseum.com exhibit, ‘The Lost Palace of Amritsar’, to find out more about the history of one of the jewels of Sikh architecture, lost to British greed and vandalism.. The lost palace may no longer exist, but its remarkable story represents an invaluable reclamation of our Sikh heritage from the mist of time.

-------------------------------

The Lost Palace

A majestic palace unlike any other once glimmered in the waters of the sacred pool of nectar at Amritsar. Learn about what was once one of the largest and most magnificent structures of its kind at the Darbar Sahib complex. Follow the history of the lost palace and the space it occupied from its origins in the Sikh Empire, to British Rule and eventually modern times.

1854 painting of the lost palace superimposed on a modern photograph depicting the scale and location of the palace in relation to Darbar Sahib.

The Bungas of Darbar Sahib

As a spiritual and inspirational hub of Sikhism The Darbar Sahib complex in the city of Amritsar has always been a very special place for Sikhs.

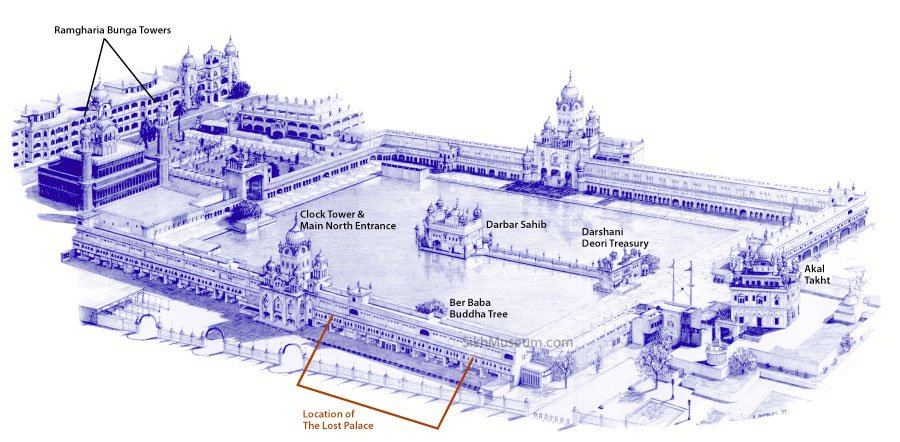

Surrounding the sacred pool of nectar at Darbar Sahib the leading members of the Sikh misls (confederacies) first established their residences and palaces (bungas) at Amritsar in the late 18th century. After a dark period, Darbar Sahib was reconstruction in 1764 after repeated destruction by Ahmad Shah Durrani and Sikhs began to enjoy a period of relative peace in Punjab where they were no longer fighting for survival as a people. With the rise of Maharaja Ranjit Singhs empire and its prosperity, at their height there were over 84 bungas around the sacred pool.

In the centre of the city of Umritsir is a gigantic reservoir of water, from the midst of which rises a magnificent temple, where the Grunth ( the holy book of the Sikhs ) is read day and night. Around this sheet of water are the houses of the maharajah, the ministers, sirdars, and other wealthy inhabitants.

Thirty-five Years in the East

L.M. Honigberger, London, 1852

Some of these palaces (bungas) were used as centers of religious teaching and education while most served as the residences of some of the powerful aind influential families of Punjab. Being on the sacred pool these palaces offered an intimate view and connection with Darbar Sahib.

Amritsar, 1859.

In the centre of the tank rose a gorgeous temple of marble, the roof and minarets being encased in gilded metal; marble pavements, fresco paintings, added to the splendour of the scene, and round the outer circle sprung up a succession of stately buildings for the accommodation of the sovereign and his court. The establishment of no noble was complete, who had not his bhunga at Amritsar.

Linguistic and Oriental Essays

Robert Needham Cust, London, 1880The Tulao, or pool, struck me with surprise. It is about 150 paces square, and has a large body of water, which to all appearance is supplied by a natural artesian well. There are no sign of the spring to be seen. It is surrounded by a pavement about 20 to 25 paces in breadth. Round this square are some of the most considerable houses of the city, and some buildings belonging to the temple, the whole being inclosed by gates: although one can look very conveniently from the windows of the houses into this inclosed space, and some of the doors even open into it.

Travels in Kashmir and the Panjab

Baron Charles Hugel, translated from German with notes by Major T.B. Jervis, 1845

Over time eventually almost all of the bungas have disappeared, being replaced by new structures; today the only two remaining bungas are the Akal Takht (Akal Bunga) and the twin towers of the Ramgharia Bunga. Although they are long gone, the palaces (bungas) of Amritsar live on in memory and are still remembered every day in the common Sikh prayer of Ardas:

![]()

Chukiaan’, Jhandae, Bun:gae jugo j-ugg atall, dharam kaa jaaekaar. Bolo jee Vaaheguroo.

May the bungas, the banners, the cantonments abide from age to age.

May the cause of truth and justice prevail everywhere at all times, utter, Wondrous God!.