BOOK REVIEW: Dr. Bhai Harbans Lal

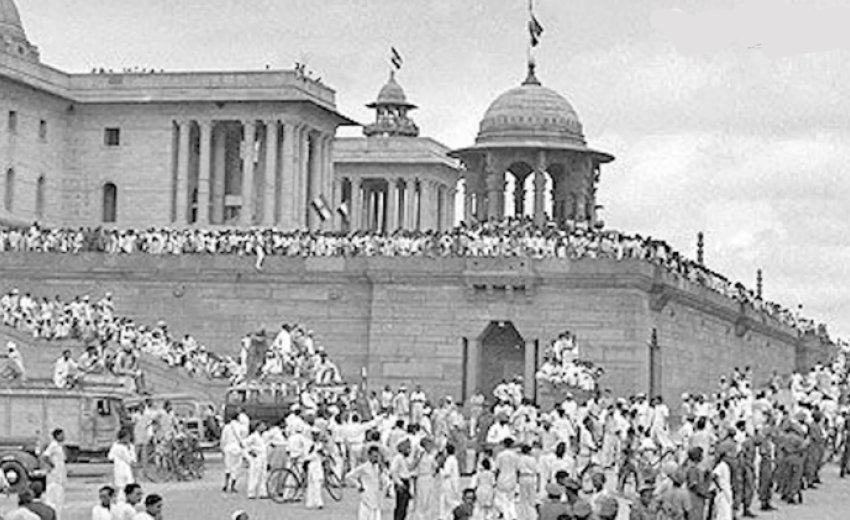

In August 1947, there was joy and excitement of India’s freedom from colonialism, but it was to be accompanied by the horrors of the country’s partition into India and Pakistan.

Sir Cyril Radcliffe, Chairman of the Boundary Commission, arrived in India on July 8 1947, with instructions to draw up a boundary line between India and Pakistan by August 15, 1947, ignoring his objections to the short time frame. In the Punjab, Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims were living so close to each other that no boundary could divide them without massive disruption, bloodshed, and destruction of valuable assets.

For the Sikhs, it would mean leaving behind their holy places and lands of origin, along with the footprints of their founders.

The Commission had four representatives; two from the Congress and two from the Muslim League, and an observer from the Sikhs. The Sikhs had no credible voice before the commission. However, the disagreement among three nations meant that the final decision was Sir Cyril’s alone.

Now, when we remember the partition of India, we feel the intense pain of a tragedy. It was the mass killing of over 2 million people besides rendering 15 million homeless. That was an enormous mass of human displacement – a population larger than some West European nations combined, indeed a displaced population that may inhabit more than half of the State of Texas or a little less than half of the State of California.

Indeed, a tragedy of that magnitude, and without precedent, must take some doing to heal. Alas, very little is being done. Seventy years have passed, and we must make an account that the wounds are not healing. The volume I am reviewing exactly narrates that.

Revisiting India’s Partition is a multi-author appraisal of the 70-year old political event turned into a tragedy by inept Indian politicians and short-sighted British rulers.

The senior editor, Amritjit Singh, is the Langston Hughes Professor of English and African American Studies at Ohio University. Singh has well over a dozen books to his credit on African American, Ethnic American, and South Asian topics. He has received many awards for his scholarship and prestigious fellowships. His collaborators—Professor Nalini Iyer of Seattle University and Dr. Rahul K. Gairola of IIT-Roorkee, India—are also well-published scholars.

The book explores the consequences of the Partition in nooks and corners of South Asia. The authors express concern with the continued negative impact of the 1947 tragedy upon all of South Asia today, especially India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. As Singh put it in an interview with the Ohio University Arts and Sciences Forum: “We are still bleeding with daily acts of violence and hatred, still coping with what happened in 1947 and again in 1971. Besides, there continue to occur new tragedies of sectarian violence. Either we are in denial, or we take shelter in a non-stop blame game.”

There are 19 essays on diverse topics ranging from the Northwest of the Indian subcontinent to the Northeast, and from J&K to Hyderabad. They underscore the continued prejudice, violence, and mistrust among groups of people displaced as well as among their newly designated hosts. The unwelcome and unfamiliar faces became sudden neighbors to millions of hosts in the strange lands.

For Singh and his co-editors, this unique interdisciplinary volume aims “to shed new light on how British India’s 1947 partition and its sectarian consequences have had an enduring impact on the peoples of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.” Thus, the volume brings together not only new readings of many literary and film texts associated with the Partition, but it also covers topics never explored in this context.

The unique interdisciplinary volume aims “to shed new light on how British India’s 1947 partition and its sectarian consequences have had an enduring impact on the receiving hosts. ” Thus, the volume brings together not only new readings of many literary and film texts associated with the Partition, but it also covers topics never explored in this context. These topics include Sindh and Sindhis, the challenges of Kashmir, border and refugee issues in the Northeast, the Long Burma March of 1941, the “police action” in Hyderabad and on the post-colonial politics in Pakistan and Bangladesh. It recasts Partition narratives in commercials by Google and Coca-Cola.

Two companion books, LOST HERITAGE: The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan and THE QUEST CONTINUES; Lost Heritage – The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan by Amardeep Singh, recently described the irreplaceable Sikh heritage that was all left behind in Pakistan by millions of Sikhs due to the painful partition of India. These books “delved into the vestiges of a community, which was impelled to move eastwards” from the land where the Sikhism was born’ and where the Sikh ancestors flourished between the 15th and 20th centuries.

In the book under review, five sections comprise nineteen chapters. The section titles speak for themselves: I. Approaches to Partition; II. Nations and Narration; III. Borders and Borderlands; IV. From Pakistan to Bangladesh; V. Partitions Within. There is plenty here to mull over. Each reader will find his or her favorite essays.

I was especially impressed by the feminist perspectives offered by Parvinder Mehta in Section I and by Tarun Saint’s analysis of partition memoirs in Section II. The essays on Sindh, Jammu & Kashmir, the Northeast, and the “the Forgotten Burma March” in Section III highlighted aspects often not deliberated as the shadow of the 1947 Partition. Similarly, the five essays in Section IV on Pakistan (issues of national identity) and Bangladesh (the 1971 massacre of East Pakistani Muslims by the Army) attempt to frame issues surrounding the Partition in new ways.

Poet Kaiser Haq’s essay was exceptionally informative and moving in its commentary on the 1971 tragedy. That tragedy inspired Intizar Husain to write his novel Basti and other writings—the subject of the beautiful essay coauthored by Dr. Tasneem Shahnaaz (Delhi University) and Amritjit Singh. My colleague, Dr. Masood Raja of U of North Texas, introduced the multiple messages of Baazigar—apparently the longest serialized novel in Urdu.

For me, the fifth and final section is especially critical to the goals of the volume under review. This section contains essays by Jeremy Rinker on Banaras, Nazia Akhter on Hyderabad, and Nalini Iyer on South Indian novels on the Partition. It demonstrates that the impact of the Partition has traveled well beyond the areas defined by undivided Punjab and Bengal, the two regions that were directly affected by the Partition violence.

The final section helps us in some ways to understand what happened sadly to Sikhs in North-West India including Delhi in 1984 and to Muslims in Gujarat in 2002. Ethnic hatred, greed, and opportunism are diseases that have infected both Pakistan’s and India’s body politic. The book’s message is clear: such repeated cycles of violence are both tragic and dangerous not just for India and Pakistan but all of South Asia.

I wholeheartedly endorse the aims the editors have had in mind. I hope their work will create new conversations and perspectives not just on Partition and South Asian Studies, but also about patterns of violence and unresolved border disputes throughout the world. Like Singh, I too hope that Revisiting India’s Partition will “help combat the erasure of cultural tragedies like genocide and displacement, especially for historically marginalized peoples” throughout the world. We have all been watching the fate of Syrian refugees and Rohingya genocide in recent months. However, the challenges of refugee populations are common in many other parts of the world, including Palestine and Southern Africa.